- Goose

- Cogito ergo sum

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 1/29/2015

- Posts: 13,427

Examining the Artists of the Revolutionary Era

Examining the Artists of the Revolutionary Era

By VIRGINIA DeJOHN ANDERSON DEC. 2, 2016

OF ARMS AND ARTISTS

The American Revolution Through Painters’ Eyes

By Paul Staiti

Illustrated. 389 pp. Bloomsbury Press. $30.

A REVOLUTION IN COLOR

The World of John Singleton Copley

By Jane Kamensky

Illustrated. 526 pp. W.W. Norton & Company. $35.

One chilly December day in 1818, a skeptical John Adams entered Boston’s Faneuil Hall to view a painting. In his opinion, artists who depicted grand historical scenes, such as the image he had come to see, often distorted the truth and in so doing “conspir’d against the Rights of Mankind.” Adams did not report his reaction to this particular picture, but he almost certainly disapproved. The painting in question was John Trumbull’s “The Declaration of Independence,” which currently hangs in the rotunda of the United States Capitol.

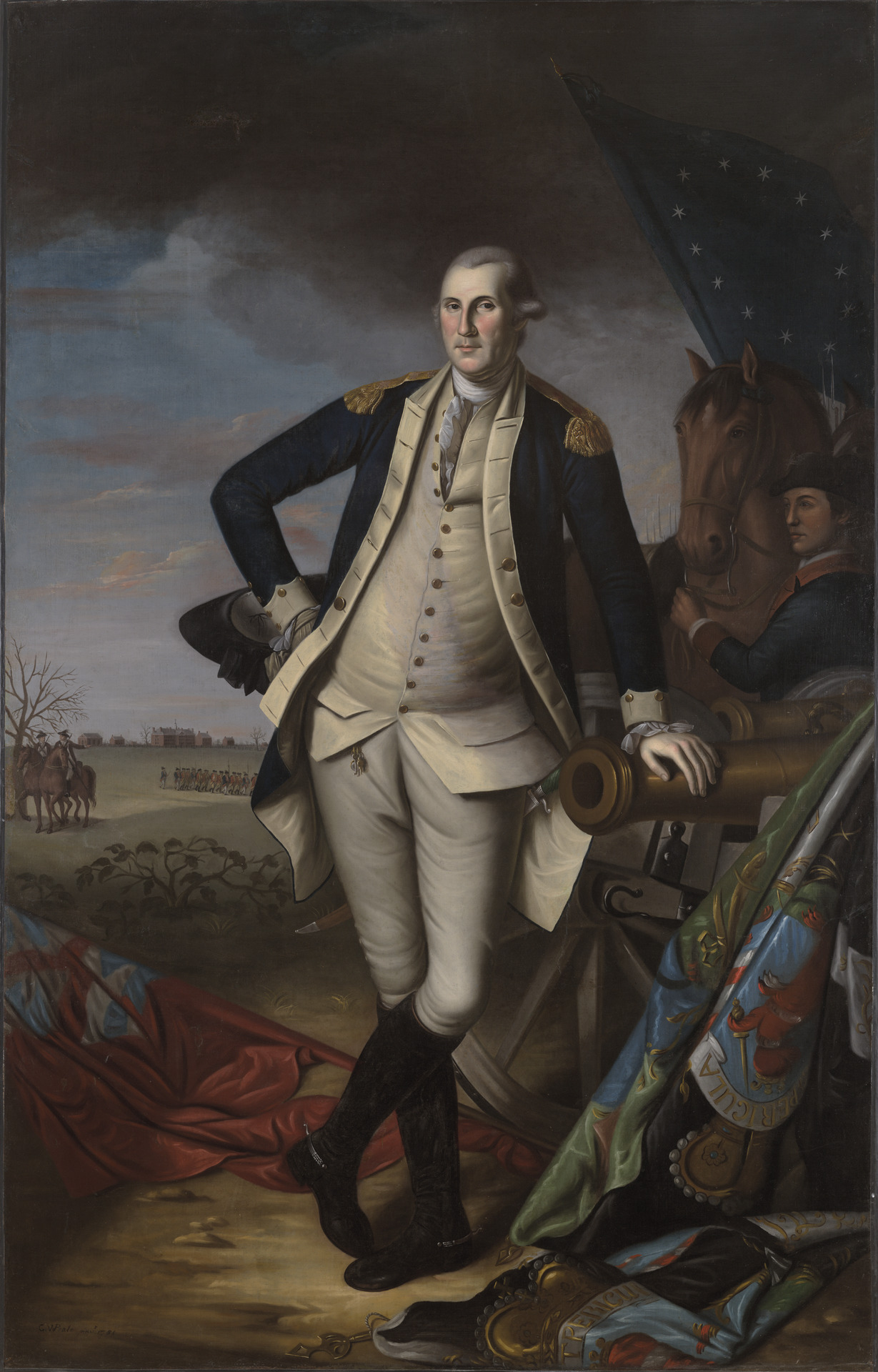

Trumbull’s representations of key Revolutionary events, along with portraits by Trumbull and his contemporaries of such figures as George Washington, Samuel Adams, Paul Revere — and, yes, John Adams — now enjoy iconic status as a visual record of America’s founding. These images testify to the talents of a remarkable coterie of artists whose lives are explored in two new books.

Paul Staiti’s “Of Arms and Artists: The American Revolution Through Painters’ Eyes” examines the careers of Charles Willson Peale, Benjamin West, John Singleton Copley, John Trumbull and Gilbert Stuart.

In “A Revolution in Color: The World of John Singleton Copley,” Jane Kamensky focuses her gaze on one of these men, whose world was turned upside down by American independence.

Aspiring colonial artists faced daunting obstacles, including a lack of both skilled mentors and access to museums with exemplary works by ancient and modern masters. Staiti, a professor of fine arts at Mount Holyoke College, reveals how some painters strove to offset these disadvantages. Initially apprenticed to a saddle-maker, Peale took art lessons from a second-rate limner. Stuart learned how to draw faces from an untrained but naturally gifted African slave. Kamensky, a Harvard historian, describes a young Copley earnestly studying engravings of anatomical images, all the while worrying if he would ever realize his lofty goals.

The solution to this predicament was to go to London. Sooner was better than later, as the career of Benjamin West demonstrated. West left Philadelphia in his early 20s and never looked back. Honing his skills in the company of such eminences as Sir Joshua Reynolds, West specialized in epic historical themes and rose to the top of Britain’s art world. A founder of the Royal Academy, he became court painter to George III — an astonishing trajectory for an erstwhile provincial. Other colonial artists eagerly sought West’s patronage once they made it to the metropolis. In Copley’s case, however, what Kamensky identifies as an idiosyncratic “blend of caution and ambition” led him to postpone his trans-Atlantic journey and instead ship paintings to West for display and critique. By the time the 35-year-old Copley sailed at last in 1774, he was too set in his ways to achieve the painterly effects that might have earned him the high praise from London connoisseurs he desperately craved.

West’s royal appointment protected him from the financial distress that plagued the others, especially in colonial settings where art was more business than calling. American patrons preferred portraits to allegorical or historical subjects, and often demanded a degree of verisimilitude that stifled any impulse to artistic license. Paintings took a long time to complete and rarely generated enough income, forcing artists to seek revenue from cheap engravings of their work. Trumbull went so far as to solicit subscriptions to prints based on paintings he had not yet begun. In London, Copley’s schemes to charge admission to exhibits of his work cost him the respect of critics who disparaged his entrepreneurialism, which eventually lost him money. Stuart repeatedly fled his creditors and sometimes sold paintings to buyers other than the patrons who had commissioned them.

When the Revolution erupted, these artists dispersed into various political camps. Only Peale and Trumbull staunchly supported the American side. Stuart remained “politically apathetic” throughout the conflict. West may have harbored sympathies for the rebels but suppressed them to retain royal favor. Marital ties to a prominent loyalist family shaped Copley’s allegiance, although he always insisted that he left Boston for Europe in 1774 to seek artistic advancement rather than escape political upheaval. Even so, as Kamensky shows, he remained conflicted to the end, bitterly fighting to retain his abandoned Boston property while struggling to reverse the downward slide of his professional fortunes in England.

These fine books approach the topic of Revolutionary-era cultural production from complementary angles. Staiti’s group portrait permits comparisons of the painters’ various paths to artistic accomplishment and reveals the mix of cooperation and competition that shaped their careers. With a singular focus on Copley and a more vibrant prose style, Kamensky probes deeply into such matters as family relations, local politics and the psychological costs of failing to realize one’s ambitions.

The authors occasionally diverge in their pictorial interpretations. Take Copley’s famous “Watson and the Shark.” Staiti argues that Copley, adopting the style of Italian Renaissance masters, “aggrandized Watson’s personal adversity” to emphasize “heroic valor, with Christian overtones.” For Kamensky, the painting represents “a parable of redemption.” By commemorating the rescue of a drowning boy in Havana Harbor in 1749, the image alluded to Britain’s 1762 naval victory in the same setting. Copley first exhibited it in 1778 as the tide of the Revolution turned in America’s favor, offering viewers “an image of a war in which Britain might still prevail.”

“Watson and the Shark” convinced at least one English critic that the Boston-born Copley could be counted as one of “our Countrymen.” This statement raises the question: In what sense were these men “American” artists? All of them were born British subjects, and neither West nor Copley ever set foot in an independent United States. Kamensky acknowledges this ambiguity, noting that Copley is best known for pre-Revolutionary portraits now treasured as representations of “the spirit of an America the artist had never known.” Staiti, in the end, is less concerned with the painters themselves than with the legacy of their prodigious talents. Their collective works, he concludes, “are key elements in a visual repertory that Americans can call upon in order to understand where the nation came from and in what direction it ought to be going.”

One can imagine John Adams scowling at such a statement. He knew that Trumbull’s painting of the signing of the Declaration did not accurately depict the event — Adams, after all, was there. The stunning portraits now gracing the walls of American museums, as often as not, showed subjects as they wished to be seen, nestled in lavish settings with symbols of wealth and power. Indeed, having once sat for his own portrait by Copley, Adams later rejected the result as a “Piece of Vanity” inconsistent with genuine republican virtue. Any lessons posterity might have derived from this visual corpus misrepresented a Revolution that was far too contentious and rough-edged to be captured by the smooth application of paint to canvas, however skillful the wielder of the brush.

Adams had a point. The visual record of the Revolution commemorates eminent founders, not ordinary participants, and the signing of documents rather than the quarrels that accompanied their composition. It is, however, the only visual record we have. These paintings may not make manifest all dimensions of a tumultuous Revolution. But even Adams might agree that it is salutary for Americans to be able to picture Washington and his contemporaries keeping an eye on them.

Virginia DeJohn Anderson’s new book, “The Martyr and the Traitor: Nathan Hale, Moses Dunbar, and the American Revolution,” will be published in June.

We live in a time in which decent and otherwise sensible people are surrendering too easily to the hectoring of morons or extremists.

1 of 1

1 of 1