- Goose

- Cogito ergo sum

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 1/29/2015

- Posts: 13,427

Why Does Moses Have Horns?

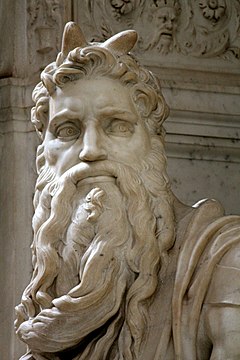

The Moses is a sculpture by the Italian High Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti, housed in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome. Commissioned in 1505 by Pope Julius II for his tomb, it depicts the Biblical figure Moses with horns on his head, based on a description in the Vulgate, the Latin translation of the Bible used at that time.

Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to build his tomb in 1505 and it was finally completed in 1545; Julius II died in 1513. The initial design by Michelangelo was massive and called for over 40 statues. The statue of Moses would have been placed on a tier about 3.74 meters high, opposite a figure of St. Paul. In the final design, the statue of Moses sits in the center of the bottom tier.

The statue has what are commonly accepted to be two horns on its head.

The depiction of a horned Moses stems from the description of Moses' face as "cornuta" ("horned") in the Latin Vulgate translation of the passage from Exodus in which Moses returns to the people after receiving the commandments for the second time. The Douay-Rheims Bible translates the Vulgate as, "And when Moses came down from the mount Sinai, he held the two tables of the testimony, and he knew not that his face was horned from the conversation of the Lord." This was Jerome's effort to faithfully translate the difficult, original Hebrew Masoretic text, which uses the term, karan (based on the root, keren, which often means "horn"); the term is now interpreted to mean "shining" or "emitting rays" (somewhat like a horn). Although some historians believe that Jerome made an outright error. Jerome himself appears to have seen keren as a metaphor for "glorified", based on other commentaries he wrote, including one on Ezekiel, where he wrote that Moses' face had "become 'glorified', or as it says in the Hebrew, 'horned'." The Greek Septuagint, which Jerome also had available, translated the verse as "Moses knew not that the appearance of the skin of his face was glorified." In general medieval theologians and scholars understood that Jerome had intended to express a glorification of Moses' face, by his use of the Latin word for "horned." The understanding that the original Hebrew was difficult and was not likely to literally mean "horns" persisted into and through the Renaissance.

Although Jerome completed the Vulgate in the late 4th century, the first known applications of the literal language of the Vulgate in art are found in an English illustrated book written in the vernacular, that was created around 1050: the Aelfric Paraphrase of the Pentateuch and Joshua. For the next 150 years or so, evidence for further images of a horned Moses is sparse. Afterwards, such images proliferated and can be found, for example, in the stained glass windows at the Chartres Cathedral, Sainte-Chapelle, and Notre Dame, even as Moses continued to be depicted many times without horns. In the 16th century, the prevalence of depictions of a horned Moses steeply diminished.

In Christian art of the Middle Ages, Moses is depicted wearing horns and without them; sometimes in glory, as a prophet and precursor of Jesus, but also in negative contexts, especially with regard to Pauline contrasts between faith and law - the iconography was not black and white. However, starting in the 11th and 12th centuries, the social position of Jews, and their depictions in Christian art, became increasingly negative and reached a low point as the Middle Ages ended. Jews became identified with the devil, and were commonly depicted in an evil light, with horns, a libelous stereotype that exists to this day. Hence many people today interpret the horns on Michelangelo's statue only in a negative light, a situation that was not true in Michelangelo's day.

A book published in 2008 advanced a theory that the "horns" on Michelangelo's statue were never meant to be seen and that it is wrong to interpret them as horns: "[The statue] never had horns. The artist had planned Moses as a masterpiece not only of sculpture, but also of special optical effects worthy of any Hollywood movie. For this reason, the piece had to be elevated and facing straight forward, looking in the direction of the front door of the basilica. The two protrusions on the head would have been invisible to the viewer looking up from the floor below — the only thing that would have been seen was the light reflected off of them." This interpretation has been contested.

(Michelangelo)

Last edited by Goose (5/28/2016 1:10 pm)

We live in a time in which decent and otherwise sensible people are surrendering too easily to the hectoring of morons or extremists.

1 of 1

1 of 1